Chapter 81. Father Locates Us

That summer, Father located us, rather fortuitously. He had met an old friend of Paul’s in Havana, quite coincidentally, in the street. The friend, named Besner, told Father, upon learning his name, that he had a friend Paul Rosegg who was living in Nice with a boy whose name was also Mechner. That was when he found out that we were still alive. Since Besner didn’t have any address, Father’s next challenge was to track us down. The circuit of contacts through which he did included my grandparents who were still in Vienna, Tante Louise on the Plateau d’Avron, and Lucy Feingold in Vichy.

Lisa told me that even though we could once again exchange letters with my parents, an early reunion was still highly unlikely. But in my heart I felt that it couldn’t be far off. I thought I knew something that no one else knew or would believe, namely that Father was a genius whose willpower enabled him to accomplish anything he wished. That conviction was reinforced by our receipt, soon afterwards, of a package of white bread, hard-boiled eggs, and lard that my parents arranged to have sent to us by a Portuguese company. The value to us of that package was unimaginable. We rationed its contents over several weeks, and shared some of it with starving friends.

Toward the end of the summer the Jewish refugees in Nice were disturbed to see occasional Nazi motorcycles on the Boulevard des Anglais. Everyone knew that Maréshal Pétain was a Nazi puppet, but his deal with the Nazis was supposed to have kept them out of southern France. So, what were they doing here? To the seasoned eyes of the refugees, this type of activity seemed like the usual prelude to the rounding up of Jews by the Gestapo. We conveyed our anxiety to my parents. We knew and they knew that our lives were once again in ever-increasing danger.

In July of 1941 Father wrote us that he had found a way to get me to Havana. I had known all along that he would come through. He had managed to enlist the help of an official from the Cuban consulate. I would receive the visa and then we would have to find someone who was traveling to Havana and would consent to take me along. One or two months were spent trying to find such a person. Unfortunately, the few candidates who could be found were understandably unwilling to take on such a responsibility. Time seemed to be running out.

But then Father came through again. In September he wrote that he had succeeded in getting a Cuban visa for Lisa too, and that she and I would be able to come to Cuba together. From that time on, my excitement at the prospect of imminently rejoining my family dominated my thoughts. Everything else — hunger, stamps, school — became secondary. I felt that once again I had been miraculously saved, and experienced a feeling of free-floating gratitude and obligation to the world.

Chapter 82. We Start the Trip

We began our trip to Havana in late September. First we had to go to Marseille to pick up our visas. Lisa, Paul, and I stayed there for about a week, during which we took endless long walks around the harbor and the city of Marseille [#11 ON THE MAP]. I also spent a lot of time with a new friend I made there, Kurt, the son of Jewish refugees who lived in Marseille. Kurt and I shared a passionate interest in airplanes and the history of aviation.

Once our paperwork was in order and we had our visas, Lisa and I got on the train to Saragossa, Spain, where we would change trains for Madrid. Our destination was Lisbon, which we would reach just in time to catch the Portuguese ship Nyassa, which was supposed to be the last boat to Havana.

As we said good-bye to Paul through the window of our train compartment, he informed Lisa that, unfortunately, our luggage hadn’t been loaded onto the train by departure time, but that he would make sure it got on the very next train, which was to leave the following day. He also handed me a paperback book, Les Chasseurs de Giraffes, an adventure story involving an African hunting expedition by Boers.

We got off the train in Canfranc, the first stop after crossing the French border into Spain, to wait for the train that had our luggage. Canfranc was a tiny village in the Pyrenées, ensconced between steep mountains. We spent the night at a farmhouse near the railroad station. I spent most of the next day outside, practicing juggling with a stick and playing with a friendly teenaged farm girl. When the train with our luggage arrived at the end of the day, we boarded it and resumed our journey.

Late that night we arrived in Saragossa [#12 ON THE MAP]. We got off, ran around a bit to retrieve our luggage. When we tried to catch the train for Madrid, we learned that it had already left. We missed it because of the day we had spent in Canfranc.

The next train, which we were told was going to be the last one to Madrid for many days, was already standing in the station. A huge crowd of desperate people was struggling to get on it. Since it was already fully packed inside, people were hanging from the doors and windows. Some were climbing up on the roof. And there were hundreds of people between the train and us, and we had our luggage to carry. There was obviously no way for us to get on that train.

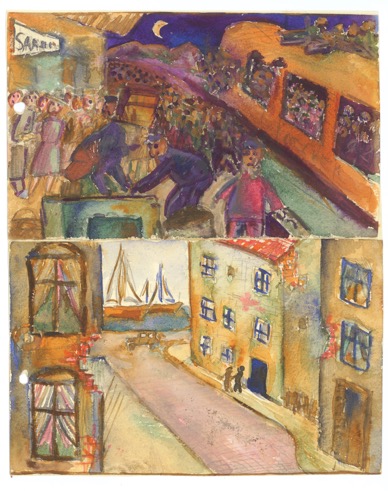

Tempera paintings I made in Havana in 1941

Top: The bedlam in the Saragossa train station. It was obvious to us that that was no way for us to get through that crowd to reach that train, and wouldn’t be able to get on it even if we reached it.

Bottom: The streets of an old quarter of Lisbon, where we took walks.

Our despair deepened as the fatefulness of our predicament sank in: Since we would not be able to reach Lisbon in time to embark on the Nyassa, the last boat to Havana, the stopover in Canfranc seemed to have cost us our last chance to be saved. Would we be able to stay in Spain? In Portugal? Would the authorities send us back to Nice?

We stood there with our luggage in the middle of the panicky crowd, unable to budge, getting jostled, crying and not knowing what to do. Lisa held on to me tightly so that I wouldn’t get separated from her or trampled. To make matters worse, I urgently had to go to the bathroom.

Chapter 83. Another Miracle

Suddenly a young man grabbed some of our luggage, told us to follow him, and violently pushed through the crowd ahead of us toward the train. When we reached the train, he shouted to some people in Spanish. They took our luggage and pulled us up into the railroad car. We had made it! It was a miracle. Our benefactor disappeared as suddenly as he had appeared, without even giving Lisa a chance to thank him. He had probably saved our lives.

On the train, I finally found a bathroom, although I was upset by how extremely filthy it was and by its lack of toilet paper. The aisles of the train were packed with people standing. Eventually, some men gave us their seats and I quickly fell asleep.

We arrived in Madrid the following afternoon and went to a small hotel. Our train to Lisbon was to leave the next morning. We were still starved, so the first thing we did was to sit down in the hotel’s three-table restaurant. Unfortunately, there wasn’t much more food in Madrid than there had been in Nice. All we could get was bread, and I stuffed myself with it. I hadn’t had bread in quite a while.

We went back to our room and, utterly exhausted, I promptly fell asleep. Although Lisa badly wanted to get to the Prado museum before it closed, she waited for me to wake up. When I finally did, we rushed right over, but it had just closed. So we took a long walk around the boulevards of Madrid. A street photographer took an unsolicited picture of us and tried to sell it to us. Lisa told him, sadly, that we didn’t have any money to buy it. In the evening, our hotel was able to get us a small portion of meat and potatoes, which I devoured eagerly.

The next morning we took the train to Lisbon. From the window of the train we saw beautiful mountain landscapes, some of which I drew with my crayons. As we passed through Portugal, we stopped in a railroad station in which people were dancing and playing music.

“You see, this is a country where people are happy,” said Lisa, “not like the places we have been lately.”

Chapter 84. We Miss Our Boat

The day we arrived in Lisbon, the stresses of the trip took their toll on me and I came down with a high fever. When the authorities learned that I was sick, they would not let us board the Nyassa, which was scheduled to leave the next morning. Again, we were in despair as we believed that the Nyassa was the last boat to Havana. But then, to our great relief, Lisa learned that there was going to be one more boat to Havana in about a week, the Villa de Madrid, absolutely the last boat for many months.

Lisa rented a tiny attic room with a small window and a slanted ceiling, in a small hotel on the harbor. We desperately hoped that I would recover in time to catch the Villa de Madrid. I was sick for several days during which Lisa rarely left my bedside. Luckily, I recovered in time.

The first day I was well we got ourselves a decent meal and then went for a walk around Lisbon’s harbor district. It was a beautiful, sunny day in early October, and I thought that I had never in my life felt so well, so energetic, and so happy.

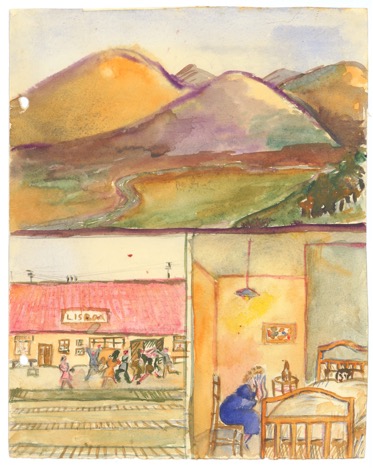

Tempera paintings I made in Havana in 1941, to illustrate the first draft of this memoir.

Top: A mountain landscape I saw from the train window on the trip from Madrid to Lisbon.

Bottom left: People dancing in a train station as seen from the train window during one of our station stops in Portugal. Lisa commented that we are finally in a country where people are happy.

Bottom right: Lisa sitting by my bed during my illness in Lisbon.

As Lisa stood on line at the ministry to complete our paperwork for embarkation, the man standing in line behind her told her that, looking over her shoulder, he had seen the name Mechner on one of the documents she was holding, and then had heard her give my name when she was called by the clerk.

“Is that any relation to Adolf Mechner?” he asked her. It turned out that he and Father had gone to elementary school together in Czernowitz, Romania. The man was Bernard Reder, the famous sculptor. Reder told Lisa that he had just been released from a Spanish prison, which was the reason for his crew cut, and that he and his wife were also going to Havana on the Villa de Madrid.

Chapter 85. The Voyage to Havana

We embarked on September 20, 1941. As our boat pulled away from shore, Lisa and I looked at the receding shoreline from the ship’s railing. The hills became smaller and hazier as we pulled out to sea.

“Take a good look, Franzi,” said Lisa with tears in her eyes. “It will be a long time before you see Europe again.” I had a lump in my throat, as I knew only too well what she was talking about. Since I had left Vienna three years before, I had yet to revisit a place I had left.

I soon became seasick and stayed that way for the next twelve days. Traveling third class, we slept in a bunk bed in a smelly area shared with sailors and other third-class passengers, but spent most of the days sitting on the deck where we visited with Reder and his wife, who were in first class. Since third-class food was either inedible or non-existent — I don’t remember which — the Reders brought us their first class leftovers every day. However, due to seasickness, I had trouble holding anything down.

But that didn’t keep me from drawing. Lisa took out my pencils and drawing pad, and I drew while sitting on the floor of the deck. Reder was impressed by how I drew and recalled that Father also used to draw very well as a child. While sitting in his reclining beach chair, Reder made drawings for me of complicated things like horses and circus acrobats. I had never before seen anyone draw so well. Reder sometimes coached me as I drew, revealing whole new vistas to me.

My other major activities during the trip were to read and reread Les Chasseurs de Giraffes (twenty five times during the boat trip) and to watch the dolphins and flying fish alongside the boat.

Chapter 86. Our Arrival in Havana

On October 3, 1941, the Villa de Madrid pulled into Havana harbor. As it did, I spotted my parents and my sister, Johanna, standing behind a gate with a large crowd of people. Lisa was skeptical that I could recognize anyone at such a great distance, even though she knew that I had “telescopic eyesight.” She said that she couldn’t even make out the people. I told Lisa that I was sure that I saw Johanna jumping up and down while holding on to the gate. As the ship pulled in, Lisa saw them too.

My joy was now complete and my fantasy of the past three years realized. I had to keep reminding myself that this time it was real and not just a dream. Though I knew that I had been granted a new lease on life, I felt willing to settle for just another few years. I didn’t want to be greedy by demanding to live to adulthood, much less to old age.

While disembarking, we were told that we wouldn’t be allowed to get close to anyone until we had been quarantined for twelve days in the internment camp Tiscornia, to make sure we were not carrying in any communic¬able diseases. I found this quite frustrating, as I had thought that bliss was only minutes away. “We waited three years, so we can certainly wait another twelve days,” said Lisa to console me. As it turned out, we spent only three days in Tiscornia. Through Sr. Agramonte, Father got us out early.

While we were in Tiscornia, my parents found a way to visit with us through at the iron bars of a huge locked gate through which they could hand us things. Mother was shocked by my emaciated appearance, made even worse by the preceding twelve days of seasickness. She brought us oranges, pineapples, and bananas, which I devoured and could never get enough of.

Just as exciting as the food were the tropical butterflies that I had been reading and dreaming about since Vienna. Here they were, not on the pages of books, but actually flying around! I spent my days chasing them all over the camp grounds. Not being permitted to drink the Havana tap water, I was constantly thirsty.

On one of her visits, Mother made some derogatory remarks about my old sandals and later brought me new ones. I felt sad parting from those loyal old sandals, which Jacques Ziegler had bought for me in Paris and which had taken me through the streets of Vichy and on the long excursions in Nice. But all such nostalgic thoughts were overwhelmed by the euphoria I felt in anticipation of the blissful new life that awaited me.